Winter School 2019: Dissensus

The Annual Winter School, a joint project of the Centre for Humanities Research at the University of the Western Cape, the SARChI Chair for Social Change at Fort Hare University, the Interdisciplinary Centre for the Study of Social Change at the University of Minnesota, and the Jackman Humanities Institute at the University of Toronto will be held from 1 – 4 July 2019 in Cape Town under the term Dissensus. This year’s title which will order the interventions and discussions of the Winter School, is drawn from Rancière, and will cohere three distinct thematic inquiries.

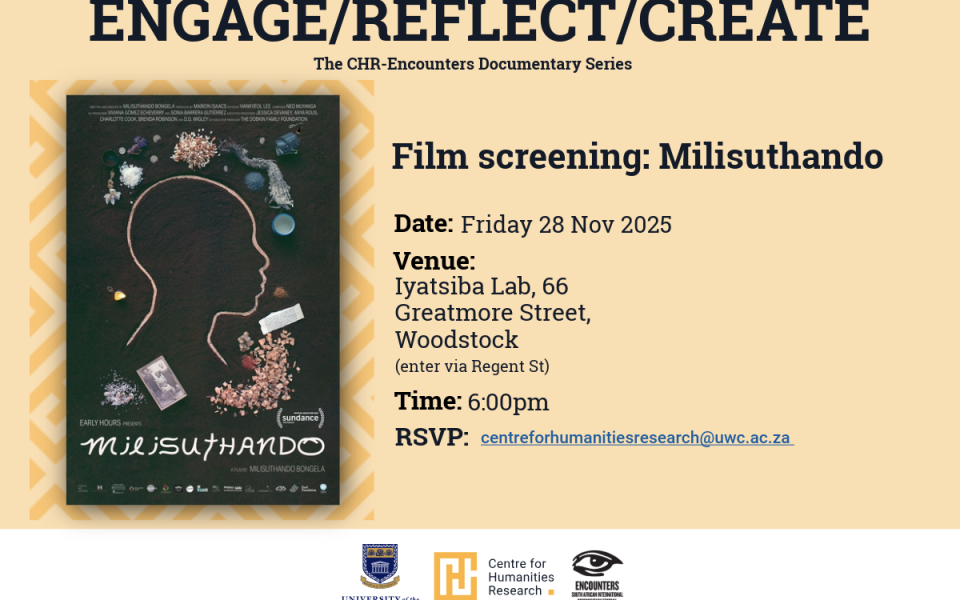

Sound and its Aftermath

A Working Group on Sound and the Humanities (SARChI Chair and CHR)

Much like many other reorientations in the humanities, the auditory turn has asked for a different relation to its disciplinary object and has called for attention to be paid to how the sense of sound in all its actualisations has permeated how we think through the predicaments of the human condition. Sound studies as a formation of late cultural studies has also raised the question of disciplinary inheritance insofar as its inquiry is located at the intersection of musicology, ethnomusicology, cultural studies, critical theory, and popular music studies. It is in these formations that sound studies recruits its techniques and conceptual grounding from; whether it be the soundscape to account for spatiality, or the audit to reorient the gaze. This inheritance and its discursive contours play out in particular ways in relation to colonial pasts and postcolonial presents, and it is in relation to what has been called the global south that the object of sound studies should be questioned.

With that in mind, we ask what it would mean to place sound in relation to the questions of subjectivity, the politics of voice, and the impasses, crises, and predicaments of lived experience in the aftermath of colonialism and apartheid. In the same breath, we are interested in what it means to take account of — or, to follow John Mowitt’s suggestion, to audit — both sound studies and the study of sound in Africa. By positing audition as a central mediating concept, we seek to implicate sound in the work of critical inquiry in the wake of colonialism and apartheid, but also to slow the rush toward any disciplinary home we might inhabit prematurely; be that sound studies, musicology, ethnomusicology, popular music studies or any other site of inquiry that marks and is marked by the intellectual inheritance on the continent.

We imagine this constellation as a space in which we might wrestle with some of these questions, in relation to our own research projects as divergent interventions located at the juncture of the network referred to as sound studies.

Democracy: Genealogies, Concepts, and Practices

Democracy is the prescribed political system of our times that promises to realize widely shared egalitarian aspirations, desires for political freedoms, justice, and sovereignty of ‘the people.’ In the present conjuncture, representative democracy has brought figures like Trump and Modi to power for example. At the same time, regime change and illiberal measures continue to be advocated in the name of democracy for certain parts of the world. While advocates of democracy are seen to be protecting alliances with those who view democracy with suspicion, democracy is being mobilized as the grounds upon which to remove others or so-called outsiders from the benefits of equality or citizenship.

Democracy as historically inflected, concretely manifested, and abstractly legitimated appears therefore more as a question to be understood than an answer to be taken for granted. We thus believe that the moment is opportune to think about democratic futures in relation to the democratic, and the illiberal aspects of our present and past and the constitutive relation between the two.

Traversing the terrain between theories of democracy and political practices, the thematic inquiry is interested in the relationship between templates of republican democracy inherited from colonial modernity, the nature of popular sovereignty they afford, the ideas of inclusion they promised, and the forms of authoritarianism, economic challenges, political conflict and state violence they experience. Are political conflicts and violence constitutive of majoritarian democracy framed within the nation-state? How do modern democratic systems accommodate various forms of political and social marginalization, structural and physical violence while maintaining their legitimacy? What might we learn about our received democratic models when we examine the “darker sides” of political life constituted between histories of progress co- existing with legacies of colonies?

Art, aesthetics, politics

The aesthetic—simply put, perception by sensation—has long been recognized as a site of multiple discriminations, only three of which will be noted here. Firstly, taking place at the surface of the human subject, where it ends and where objects and others begin, the human sensorium poses the most rudimentary, yet never fully resolvable, questions concerning inner and outer, subject and object, human and non-human. Secondly, and in a fairly straightforward way, the sensations registered by the body have been thought to furnish the possibility for judgment, reflection. Thirdly, relatedly, and in a manner more pernicious if only because it discloses the violence of the first two senses, the capacity for aesthetic judgment, to assume a certain distance from what affects, has been weighed on a developmental and evolutionary scale: at the low end the scale registers a “primitive” domination by sense, pleasure, in short a proximity to nature; at the upper end the proper mediated distance of “civilized” reflection. The discriminating social function of the aesthetic replicates, here, in the division of the faculties of the subject in judgment— the senses, the imagination, which is thought to represent sensory intuitions to the cognitive faculties—a division of labor according to which nature has been brought into a relation of progressive domination: just as natural resources are extracted from the earth for processing, so sensory intuitions stand as a kind of “raw material” given over to the cognitive faculties; insofar as the colonized were cast as being in a natural, “untutored,” raw state, their domination became synonymous with the exercise of sound judgment itself—when Fanon writes of the “damned of the earth” and of “psycho-affective disorders” he refers to one and the same complex as it expresses itself on two different planes that must be thought in their reciprocal relation: affect is to the abstractions of reason what nature is to that of exchange value. The aesthetic, in short, cannot be disentangled from the colonial situation within which the colonized are incorporated into aesthetic discourse not simply as potential universal subjects with a latent capacity for reflective judgment, but as carriers of a corporeality against which reflective judgment can emerge at all. As such, an aesthetic education in the wake of colonial rule can never be a straightforward undertaking—if the problem is the politics of the aesthetic, the wager of aestheticizing politics is well known, it culminates, as Walter Benjamin warned, in Fascism. Yet if a genealogy of such an overdetermined differential mechanism must necessarily draw attention to its violence, this ought not, and indeed could never, eradicate the radical potential of artistic creation and encounters with it. Revisiting old debates, the contradictions of which have been carried right into our present day, this invitation asks participants to reflect—the word cannot but be freighted and, in the end, displaced—on the relations between art, aesthetics, and politics, and on their potential to instigate social change.