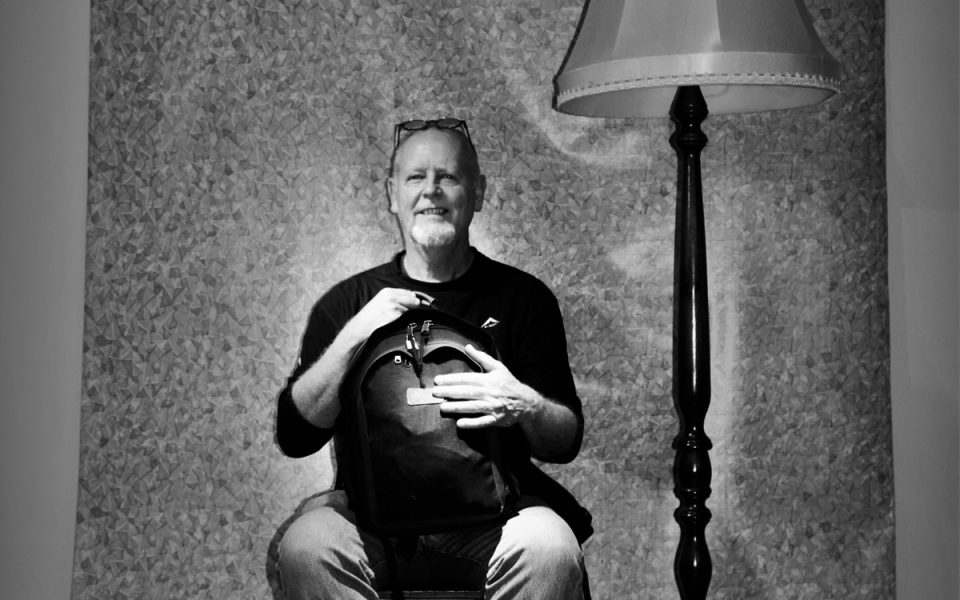

A Tribute to Paul Grendon

On 7 September 2019, prolific photographer and friend of the CHR Paul Grendon passed away. His presence in person and in his work has left an indelible mark on the CHR. Paul was an Artist in Residence at the CHR for one year. Below is a tribute delivered by Professor Patricia Hayes on the occasion of his funeral on 16 September 2019.

I have been asked to speak about Paul and his place in the landscape of South African photography. Many people unfortunately see this question of South African photography as simply divided into two parts: as one’s contribution to the struggle, or, how successfully you have been taken up by galleries, publishers and the international art market. Paul Grendon completely rewrites this simplistic understanding. In fact he shows us there are many landscapes: on the walls of cities, in people’s homes, in community museums, in the files of organisations and NGOs, sharing space with words in history books, in our laptops, in our heads, and scattered across many fragments of public memory, and fragments of the unseen.

Paul stood with many groups, crowds, families and friends to document what many felt to be important. Sometimes he stood on his own to photograph what HE thought was meaningful, and might be less intelligible, as he worked increasingly in his own photographic language. His quiet landscapes from the abandoned fields of District Six come to mind. Sometimes one gets very frustrated, even angry, that he never received the same recognition as certain other photographers. But Paul’s own principled position forces us to reconsider all of this.

I believe very strongly that we have never worked through, never processed let alone grasped, what this country and people went through before 1994. What it looked like, what went down. Perhaps it was impossible because too much was happening, it was too violent, too heavy. But photos carry the residues of time, and now more than ever, when the current generation looks for answers to our ingrained ways of violence, we need these photos more than ever, to think with. Much that was photographed then, has not even been seen. Perhaps less than five per cent of all photos that were taken, have been seen or become known, the tip of the tip of an iceberg. Many of Paul’s photos are amongst those in the bulk of the unseen, sitting like some loaded historical unconscious. We have all lost Paul, but his work will be very important for the future.

There is a postapartheid reluctance to look at the past. It’s now about the present. I want to disagree with this. For instance, I’m always baffled why David Goldblatt’s technologically magnificent landscape photo of Echo Valley in the Richtersveld, taken with his prize Hasselblad camera, highlighting foreground, middle and background, widely exhibited and published, is treated as somehow definitive – when you only have to look at Paul Grendon’s 1980s landscape of the northern Cape, with foreground, middle and background, a humble framed black and white print on the wall of Judie Smith’s house. Doesn’t this photo ask as many questions of us, of our history, of what we share?

Which brings me to Paul’s stubbornness, or negativity, even if it was against himself. Paul always said it’s not about him. He was exceptional because he thought about other people, he could step outside himself, and he cared for others. In the early 2000s I was so bold as to phone Paul to ask if myself and some graduate students (notably Farzanah Badsha) could interview him, in the effort to understand this thing called the landscape of SA photography. His reply was so adamant, so pungent, so blisteringly negative, that I had to hold the phone away from my ear. He finished by saying that me and photography don’t get on, our relationship is over. However, over time, Paul would say things in passing, sometimes to test me I think, and sometimes I could ask him things. He did resume his relationship with photography, and we are grateful, for his mode of portrayal of especially those pushed aside by forced removals and apartheid, was to work with ordinary folks to see their own grandeur, as people, in Cape Town, Usakos, and elsewhere.

To return to Paul’s negativity, and his complete subversion of the capitalism of the dominant visual economy. At the root of it is the way we penetrate each other’s lives, invading even privacy. Photography is a devil, and scholarly research can be as well. At times we pry open, and subjects can become prey. The difference is that far more often, photographers’ work brings them very close to death. This gave Paul a very fierce ethics, from which we should continue to learn. An ethics that you don’t harm people. That visibility for its own sake can be vulgar and feed a machine we don’t control. That it can be very dangerous. That it can be self-serving. And photographs should not be that. They should be poems elicited between people, between us and Paul, between us and the land, in your head and your heart.